- |

- |

2017 marks the second year of Web Directions’ ‘Transform’ event; two days in March totally focused on government services—interrogating them, improving them, and understanding the unique problems and opportunities associated with delivering them digitally.

Just like last year’s inaugural event, Transform 2017 was inspiring and engaging. You’re always up for an interesting day when the event manager of the National Museum of Canberra asks: ‘are you transformers?’

So while images of Optimus Prime and the Autobots blossom in your mind, we’ll share the prime cuts from three presentations that grabbed our attention.

Dan Sheldon: The Government IT Self-Harm Playbook.

Dan works as a technology consultant to governments and healthcare systems worldwide. He was the co-founder of the new NHS.UK digital healthcare service and he’s helped government save millions of dollars as a senior advisor to the UK Government’s CTO while at the Government Digital Service (GDS).

Dan is well-known for writing an article on Medium last year called ‘The Government IT Self-Harm Playbook’. It’s the A-Z of all things wrong with government IT, along with some useful suggestions to make things better. His presentation followed a similar framework.

First, some context.

Back in the 90s when Australia was run by a Hawke Government, we got into IT outsourcing and figured everything was awesome. The outsourcing phenomenon was revolutionary: increasing efficiency and facilitating better services for less money. Except it wasn’t and it doesn’t.

In 2008, it was reported that the UK Government spent £21 billion on IT. And all this just prior to the financial crash. Spending that amount of money on tech simply wasn’t working.

And so, the Government Digital Service (GDS) was born. The GDS was implemented to stop bad things from happening in IT; bad things like flagrant over-spending and flawed development practices. The service had the power to limit spending in government IT and could change the conversation from contract renewals to the modifications in behaviour that needed to happen sector-wide.

Dan walked us through the ABC of the GDS; here’s his little alphabet of IT horrors.

Dan Sheldon setting us up early for his presentation.

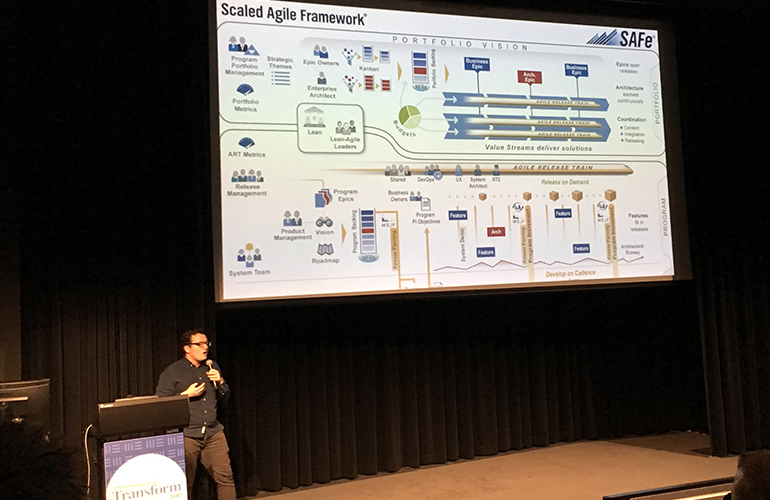

A is for Agile. Or not.

A large proportion of government services claim to be agile. Most are not. The majority work with a mixture of different principles and ultimately you can’t be half-agile and half-something-else.

According to Dan, until the way you work is based on evidence—rather than top-down control from management—you’re not really agile. Blunt, but true.

This scaled agile framework is not agile…how can it be?

B is for Business. (The).

When IT is thought of as ‘The Business’ in a government service, it’s a recipe for mutual distrust. Ideally, we shouldn’t need a dedicated IT department—everyone should be working together to achieve the same outcome, and teams should be integrated, cohesive and prioritise digital equally. The idea of an IT department defers responsibility from the rest of the people involved in providing the service, even if it’s fundamentally digital.

Sounds pretty obvious when you put it like that, huh?

C is for consolation.

There’s no ‘C’ in this alphabet, but there are two ‘D’s. Pretty sweet consolation, right?

D is for Deep Dive.

When you think of a deep dive, the ultimate scenario is to get the right people from the delivery team and the right blend of experts, working on a review of the project to make sure it’s on track, and that the team is delivering as promised and expected.

In reality however, life plays out a little differently. The senior executives call a meeting with the delivery team. They ask the team to come and meet them. The executives ask the team various questions to determine whether they can be trusted or not. It’s a disheartening and demotivating experience, even on paper. So why does it happen?

Instead, Dan recommends changing the dynamic; ask the senior executives to come to you. Show them the work in action, provide a view into what’s going on and the progress being made.

D is also for Delivery.

There was an oft-quoted phrase at the GDS:

The strategy is the delivery.

Previously, government in the UK had been known to produce strategy after strategy without ever delivering any tangible value. Government is not a start-up. It exists in the real world, and the services we expect government to deliver can’t be shipped simply like a book or a new iPad.

Government delivers at all costs. This isn’t good. Government services should be, and need to be, planned, researched, and well executed in order to be effective. Copious amounts of strategy does not breed trust within a government organisation, nor with its customers. Careful planning, open dialogue, thorough research and solid execution however, does.

G is for Go-Live.

Ahh, that antiquated phrase… the Go-Live.

Dan made a good point here; government services shouldn’t be ‘launched’. They should always be live, iteratively evolving and constantly improving in the way they’re provided.

We need to move beyond the static concept of the ‘go-live’. When you think about it, a go-live is just a launch at a particular point. It’s not the be all and end all.

N is for Nominative Determinism.

What’s that, you say? But ‘what’s in a name?’ may be the better question. And the answer is: your future.

Nominative Determinism is the idea that people gravitate towards areas of work that fit their names. The same is true of titles and businesses. For example, someone with the job title ‘Primary Executive of Quality Assurance and Standards’ may approach their role differently than someone with the title ‘Tester’.

Nominative Determinism is closely linked to Conway’s Law, or the idea that:

‘Organisations are bound to produce products which reflect the way they are structured.’

Think about that for a moment. It goes a long way towards explaining some of the issues associated with government service design.

Dan’s tip is to structure your organisation or service’s name in the way that you want to be known in the future. Tie it to the problem you want to solve. Otherwise, you’re ultimately just re-building your org-chart every time you go to design a product.

P is for Platforms.

When delivering government services, it seems everything is a platform. It’s an abundant and overused term. The problem is:

Does anyone actually know what a platform is?

One of Dan’s examples of problematic ‘platforms’ involves enterprise architecture. In this case, the design of a platform was created well before the team had a full understanding of the complexities and nuances of the problem at hand.

To make matters worse, it was then mandated that all associated products should use the shared platform for that service. The phrase ‘horse before cart’ comes to mind.

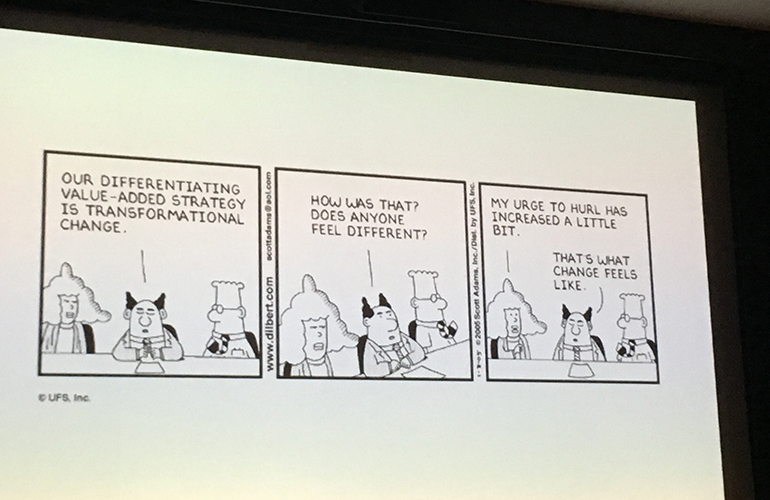

S is for Steady State.

Dan describes ‘steady state’ as a mythical nirvana. <Cue choral voices and a burst of white light>. It’s a valorised land that exists beyond our earthly state of constant disruption and unexpected change.

But like all myths, the steady state doesn’t actually exist. It never arrives and it’s unhelpful to continue to believe that it does—or ever will—exist.

Instead, we should work to embrace change. It’s not always easy and sometimes it’s uncomfortable, it’s disruptive and it takes time. But there’s no end point; no steady state on the horizon. The truth is that change evolves and helps you evolve.

The only constant is change.

Once you’ve gone through a period of transformation, you should begin planning further ways to improve and advance. Otherwise you’ll get left behind, fast. Believing in the concept of the steady state is believing in the concept of the comfort zone.

And if you’re in a comfort zone for too long, you’ll inevitably end up resting on your laurels.

U is for User Research.

Time and time again, Dan sees market research disguised as user research. When it comes to government services, there’s an all-too-common utterance: ‘Users say they want [insert function or feature]… so we should deliver one.’

This presents two problems:

- It doesn’t tell you how, and more pressingly

- It doesn’t offer much value.

Instead, Dan recommends seeking genuine users, customers, people… you choose the label.

But don’t assume research is only relevant at the start of a project. You need to continually engage with the people who’ll be using your service or product throughout your creation and delivery periods.

And the cardinal sin of user research? Using it to justify something you already wanted to do in the first place. Sad, but true. It happens.

Y is for You Should Check Out Dan’s Full Article On Medium.

Right here: in case you missed it the first time. Although it’s a long one, it’s well written and easy to consume. You’ll be chuckling the whole way through and you certainly won’t end up;

Z is for ZzZzzZzzZing.

(Just to finish off what was promised as an ‘A-Z’ of all things government IT).

Jenny Hunter: Will I need an umbrella today?

Next up, Jenny Hunter—Head of Digital at Bureau of Meteorology (BOM). Her presentation focused on the app BOM built and released in October last year.

Since its release, the app has had more than 1.3 million downloads nationwide and recorded more than 60 million sessions.

The app came about as a result of frequent user feedback, and not surprisingly so. The top five requests from people using the app were:

- A close button in the Android version.

- More widgets.

- The inclusion of a UV index.

- Faster load times.

- A GPS locator.

Overall, BOM has received positive reviews of the app with 70% of their feedback being feature requests.

While this sounds promising, a sobering realization followed: only two weeks of post-launch fixes had been allocated to the app but there was more work involved than a fortnight’s worth of fixes and feature requests.

Jenny needed to drive a fundamental change at BOM—to adopt an attitude of constantly making improvements to the app, rather than launching it, pushing it out to sea, and hoping for the best. (See ‘G’ in the A-Z above).

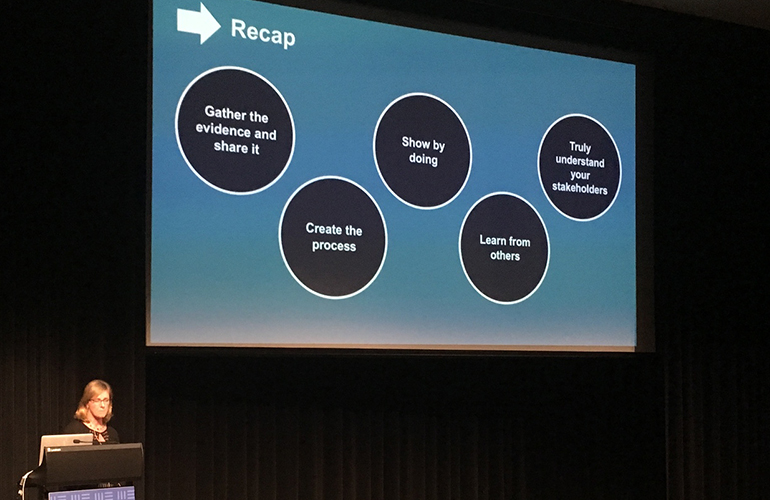

There were five themes Jenny covered in her presentation: each one a technique she used to instigate the cultural shift at BOM. The themes highlight the challenges inherent to this kind of change, and simultaneously offer some useful tips to keep in mind when working with a team.

Jenny Hunter talking us through the process BOM used.

1) Gather the evidence and share it.

First up, Jenny highlighted the important of gathering information and evidence, and sharing it—early and often. Evidence keeps people informed and involved. It’s unifying and edifying: evidence is that magical compound that keeps teams aligned, motivated and moving in the same direction. It’s proof that the team’s approach is working.

However, there’s a key consideration in the sharing of evidence: plan it out. Establish an understanding of how and when you’ll share information, so people are aware it’s coming.

2) Create the process.

In order to improve the experience for the app’s users, it was important for the BOM team to think about weather as a service. The team needed to adopt an inclusive mindset that catered to all manner of audiences, they needed to learn continuously, and they needed to put the concept of service above the concept of a platform.

The team needed to put users first—not what they thought was best for the app. As a result, the team embraced ambiguity, adopted an attitude to keep experimenting and made things simple.

Throughout, the team had to be clear on the scope of tasks, as well as the scope of the overall outcome. This was the right process for this particular project: the idea being you need to create the right one relevant for yours.

3) Show by doing.

The team had to maintain momentum post-launch. They were receiving a lot of feedback and engagement from the public around the app. However, internally, people were tired of hearing about the project. They were losing steam: BOM was going bust with motivation.

To keep things productive, the app team analysed the inbound feedback, listened to the priorities being suggested, and demonstrated what the public wanted, and most importantly, why. It wasn’t just tinkering for tinkering’s sake.

In order to get more continuous work done, the BOM team negotiated, debated and provided real data to enable updates to be completed on the app.

4) Truly understand your stakeholders.

Understanding your stakeholders in this case was not about people using the app—it was about understanding the internal stakeholders at BOM.

The team needed to ensure these people understood what was being built, and why. Keeping them informed and explaining concepts and processes was crucial to preventing difficult conversations that could erode the project.

5) Learn from others.

BOM spent a lot of time learning from other service design teams such as those in Australia Post, the Digital Transformation Agency, Transurban, and Public Transport Victoria to name a few. It was important for them to understand how others overcame common challenges and why they may do things differently.

So next time you open up the BOM weather app on your smartphone, think about the team working on this app—they’re dedicated to improving it and listen to the feedback coming in. It will be interesting to see how this app progresses in the market.

Ariel Kennan: Making public services effective and accessible.

Did you know there are 325,000 public servants who work at the New York City Mayor’s Office? There are more than 70 offices and agencies across the city and together they serve 8.5 million residents.

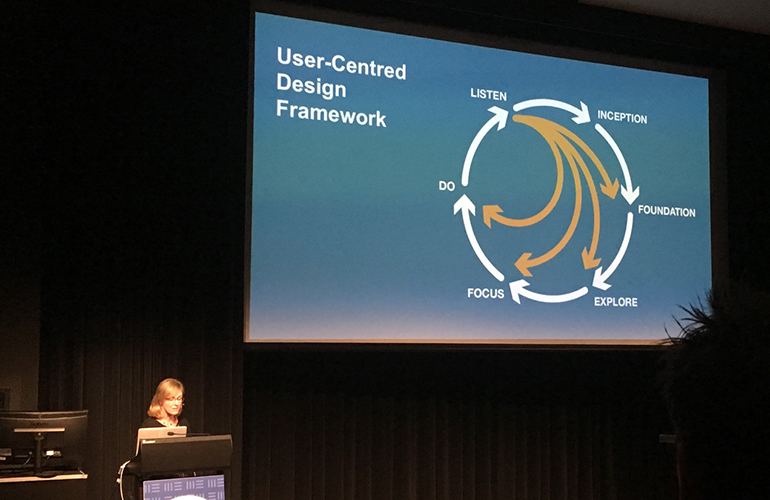

Ariel is the Director of Design and Product at the Center for Economic Opportunity at the New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations. Her presentation focused on how to do a lot with a little in a government environment, via five principles.

Here’s a quick snapshot of the five principles Ariel covered.

Principle 1: Government services should be created with the people who use and deliver them.

Talk to the people using and delivering the service. Sounds simple enough, doesn’t it?

Ariel used the example of the New York City street homeless services project she’s involved in. Created as a way to reduce homelessness in the city, Ariel and her team developed four components to work towards achieving this outcome:

- Proactive camp; people walking the streets and reporting back on what’s going on in the city.

- Adding quarterly night time counts; there is a federally mandated count one night in winter that requires all homeless people to be counted in the city but Ariel’s team wanted this count to be more frequent.

- Case conferencing and management; Ariel’s team needed to find a way to get cross agency groups to come together and talk to each other as a way to reduce homelessness in the city.

- More public accountability; in daily life and the availability of monthly public dashboards.

Ariel’s team helped connect the dots among the different government services that were working on helping to reduce homelessness. Ultimately, talking to different government stakeholders and having frequent conversations with homeless people and outreach workers helped piece together various parts of the service.

Principle 2: Government services should be prototyped and tested for usability.

An example of this principle in practice? Access NYC—the portal used for people to access their public benefits. It’s a platform that enables people to find out if they are eligible in the first place for benefits, and then run through the process of applying for them.

After extensive research and prototyping, the new portal was released March 15. It was a team effort across many different parts of government and the results came about through extensive qualitative research.

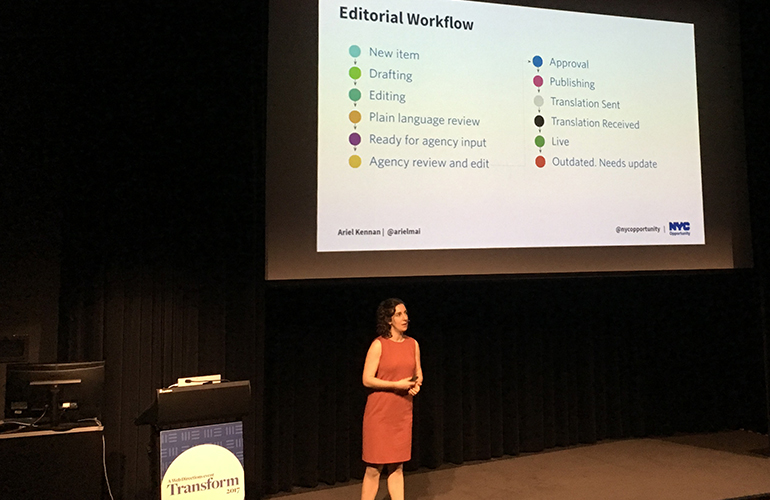

Principle 3: Government services should be accessible to all.

Ultimately, this is about having low barriers to entry. One way the New York City Mayor’s Office is working to achieve this is through content. NYC’s Open Data project puts all data in the one place and enables this content to be pushed out to various desktop apps, mobile sites and kiosks.

While there is a comprehensive editorial workflow, and the content is translated into seven languages each time something is published, the content’s key goal is to ensure everyone that’s using the content can understand it. It’s about putting in the work at the beginning to achieve a seamless finish at the end.

Ariel Kennan talking through the editorial workflow

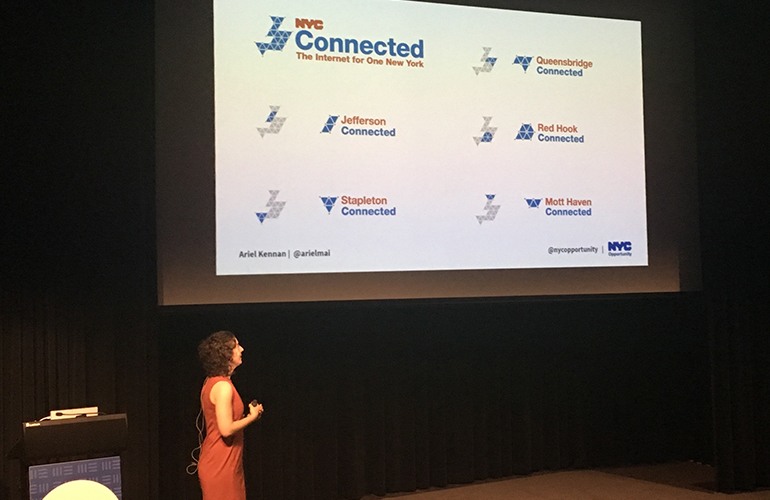

Principle 4: Government services should be equally distributed.

The New York City Mayor’s Office announced a project that would see every citizen in NYC have access to broadband by 2025. The city invested $10M USD into helping get public housing connected to broadband. Ariel’s team worked on this project and conducted a large number of user interviews so they could work with the community and understand how the residents wanted their community to be represented during this connection phase.

One of the key findings from their interviews was that hardly anyone in the community knew of the broadband investment and project that was underway. As this became more widely discussed and Ariel’s team continued interviews, putting in to practice their findings, they discovered that the Queensbridge public housing area had gone twelve months without a shooting. This is a huge achievement for the community.

Ariel’s team also found out that the project had no branding and so based on community sentiment, Ariel’s team designed a logo for the project that could be customised to each housing project. It was also a way to show progress of the connections and to help people feel connected (pun intended).

Ariel talking through the branding created.

Principle 5: Government services should be rigorously tested.

Like any service, government services should be regularly evaluated for their effectiveness and impact. If something is not working for the people using and delivering the service, it needs to change.

Ariel’s team have been working on a service design kit for government services—including assets that would commonly be used in user interviews and research.

And that’s a wrap…

This year’s Web Directions Transform was inspiring, thought provoking, and a great example of Australian government services working to be better. We’re already looking forward to see what next year brings!

More Articles

Up for some more?

Get your monthly fix of August happenings and our curated Super8 delivered straight to your inbox.

Thanks for signing up.

Stay tuned, the next one isn't far away.

Return to the blog.